A primer on Canada’s urgent human rights crisis

Written by Jody Chan, Lorraine Chuen, and Marsha McLeod

Graphics designed by Lorraine Chuen

Image: Aerial View of Edmonton Remand Centre – Canada’s largest prison at an equivalent of 10 CFL-sized football fields (Google Maps)

When we talk about mass incarceration as a crisis, we often think of the U.S. as the benchmark for disturbing trends in imprisonment. And it is: Black men are six times more likely to be imprisoned than white men in the States. The U.S. is the world’s leader in incarceration rates per capita, with a total of 2.2 million people in prisons and jails in 2015—a 500 percent increase since 1975.

In Canada, where prisons have been heralded by criminologists as the ‘new residential schools’, where the Toronto South Detention Centre has been called a ‘$1-billion hellhole’, and where Indigenous people are incarcerated ten times more often than non-Indigenous people, the crisis is also present. But here, it has been happening more quietly.

In Ontario, there are eight national correctional facilities for convicted inmates sentenced to two years or more (administered by the Correctional Service of Canada); as well as nine provincial detention centres, nine provincial jails, and nine provincial correctional centres for people awaiting trial or who are serving a sentence up to two years less a day (administered by provincial/territorial ministries, such as the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services in Ontario).

In 2016, Canada’s crime rates hit a 45-year low. At the same time, paradoxically and with resounding silence from the public, incarceration rates hit an all time high.

How many of us even know how many prisons and jails there are within 100 kilometres of where we live? 50 kilometres? 15? For example, for those living in southern Ontario—if you’ve ever been to the Ikea in Etobicoke, you’ve been just two kilometres, or a four minute drive, from the Toronto South Detention Centre.

Map of federal and provincial correctional institutions in Ontario

We have collectively subscribed to an out of sight, out of mind policy for the nearly 40 000 people incarcerated at the provincial/territorial and federal levels in Canada—over 1 out of every 1000 adults—leading to a lack of public knowledge about the inhumane conditions in federal and provincial prisons.

In this infographic series, we try to make Canada’s incarceration problem more visible by offering a snapshot of its many injustices and human rights violations.

The majority of people incarcerated in Canada are on remand—denied bail and incarcerated in advance of their trial—and therefore, are legally innocent.

Remand, sometimes called pre-trial detention, is on the rise in Canada—particularly in Ontario and Manitoba. In Ontario, the percentage of remanded prisoners (in comparison to prisoners serving a sentence) climbed 15 percent since 2000/2001 to reach 65 percent in 2014/2015. Black and Indigenous people, as well as those who were homeless or unemployed at the time of their arrest, are disproportionately not granted bail and incarcerated on remand. In 1995, the Commission on Systemic Racism in the Ontario Criminal Justice System came to the “inescapable conclusion” that some Black people who were detained pre-trial would not have been detained if they were white. This reality remains true in 2017, as do the consequences. People who are incarcerated on remand and subsequently plead not guilty at trial are less likely to be acquitted than those who were not detained pre-trial. Also, because remand is seen as temporary—despite the fact that it can stretch up to several years—prisoners on remand rarely have access to educational programming or vocational training. Prisons with a high number of prisoners on remand (usually called detention centres) are maximum security, and are often overcrowded and understaffed.

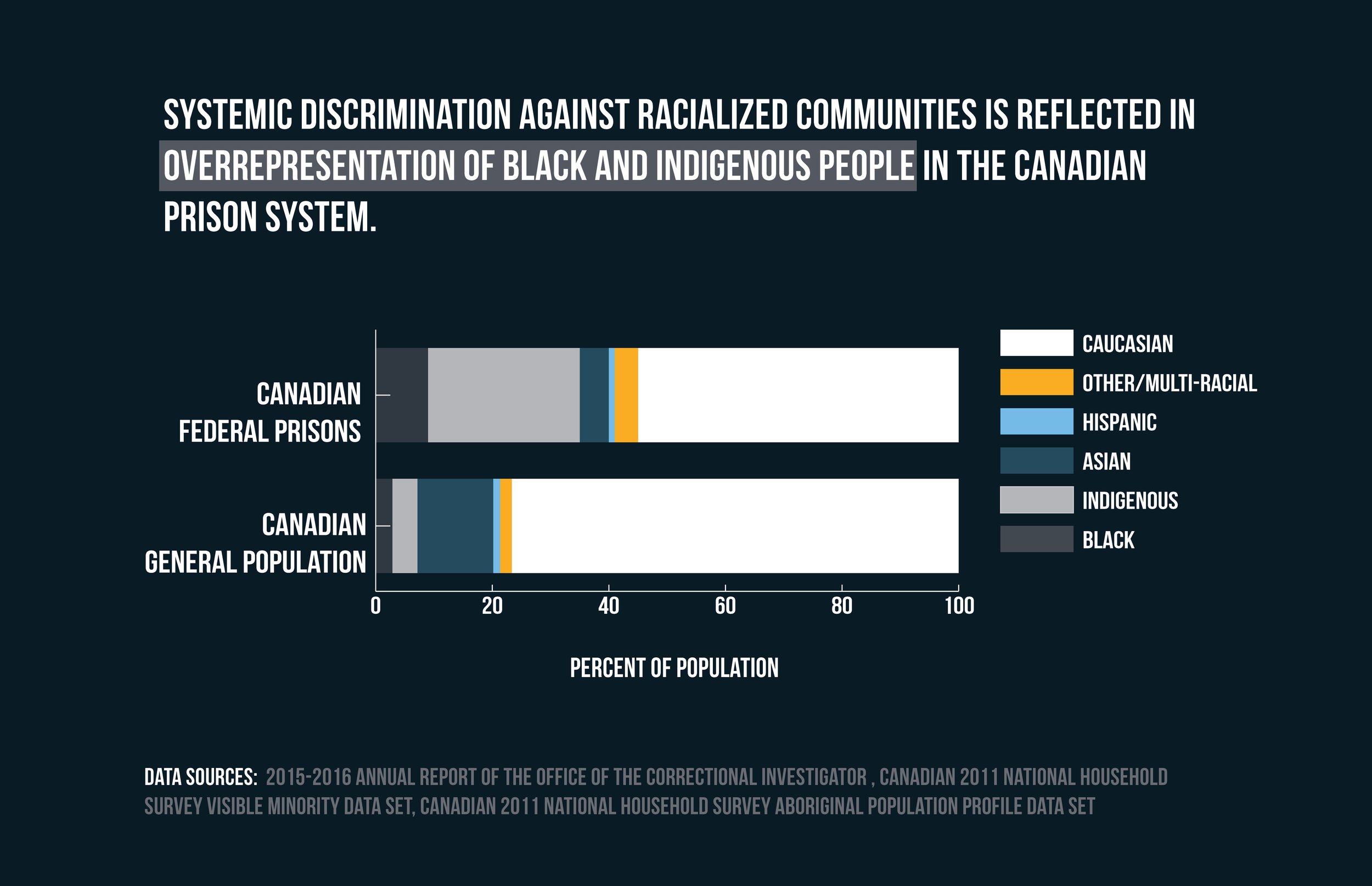

The overrepresentation of racialized communities in Canada’s prisons reflects the country’s racial profiling and over-policing of Black and Indigenous people.

Indigenous and Black people are grossly overrepresented in the Canadian prison system. Out of an average of 14 615 prisoners in Canadian federal institutions on a given day in 2015-2016, 26 percent are Indigenous and nine percent are Black—and between 2005 and 2016, the federal incarceration rate of Black people in Canada increased by 70 percent. Compare this to the breakdown of the general population: Indigenous people only make up 4.3 percent of the population, and Black people only 2.8 percent. Currently, Indigenous women are the fastest growing prison population, representing more than 35 percent of the federal population of women prisoners.

Such overrepresentation reflects how Black and Indigenous people are consistently targeted and over-policed in Canada. Data collected by the Toronto Star between 2009 and 2010 indicated that Black people were, on average, 3.2 times more likely to be carded in Toronto than white people––stopped by the police on the street, asked for identification, and having their personal information catalogued in a database—despite not being suspected of a crime. This police data was obtained by the Star through a Freedom of Information request, but most Canadian police departments don’t collect racial data on police interactions, or even actively suppress it.

This issue of overrepresentation is further compounded for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Two-Spirit (LGBTQ2S) prisoners of colour. This was particularly evident in the U.S. in the case of the "New Jersey Four." In the U.S., LGBT and gender nonconforming (GNC) youth are represented in the incarcerated population at a rate of three times the general population, and adult lesbian or bisexual women are represented in the incarcerated population at a rate of about 8 to 10 times the general population. Similar demographic data has not been collected in Canada.

**Methodological note: the demographic categories cited in the graphic are those defined in the 2015-2016 Annual Report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator. These differ from the Canadian 2011 National Household Survey (NHS) categories. In order to compare the two datasets, subgroups from the NHS visible minority and Aboriginal Population Profile data sets were re-coded to fit the Canadian federal inmate demographic categories. The breakdown can be accessed here.

Access to education and vocational training is both cheaper and more effective at keeping people from returning to prison than longer sentences or punishments like intensive surveillance or electronic monitoring.

A 2004 study by the UCLA School of Public Policy and Research found that a $1 million investment in incarceration would prevent 350 crimes, while a $1 million investment in prison education would prevent more than 600 crimes. Similarly, a 2013 report found that formerly incarcerated people who participated in education programs had 43 percent lower rates of being rearrested for similar offenses (sometimes called recidivism), and that each dollar spent on prison education translated to four dollars of cost savings in the first three years post-release. Compare these findings with the fact that it costs Correctional Service Canada an average of $111,202 annually to incarcerate one man (and twice as much to incarcerate one woman), with only $2950 of that money spent on education per prisoner. But even “re-entry” programs can fall short of eliminating the systemic barriers to accessing education and employment that target working class communities and communities of colour for incarceration in the first place.

Incarcerated people have an internationally recognized right to education; yet people incarcerated on remand are often left entirely without access.

Though the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services (MCSCS) states on their website, that educational opportunities are available “through a variety of partnerships,” in Ontario, it is not legally mandated that correctional institutions provide educational programming for prisoners. Unsurprisingly, prisoners on remand in Ontario often experience a particularly acute lack of access to educational programming, argues a 2014 research paper from academics at Ryerson University—one of very few publicly available documents on access to education for remanded prisoners. The authors cite research noting that religion and addiction support programs are the only consistently implemented programs in Ontario’s detention centres. The authors also note that the only formal educational program they are aware of in Ontario’s detention centres—Amadeusz’ The Look at My Life Project—has a long waiting list and is unable to meet demand for their services. We could not locate any publicly available data on the number of people incarcerated in Ontario without access to educational programming. We also could not locate any data MCSCS’ educational spending.

At the federal level, the CSC is doing little better in addressing the educational needs of prisoners (75 percent of whom are without a high school diploma)—despite a legal mandate to provide education. For example, the CSC itself has noted that they must better address the needs of prisoners with learning disabilities, and improve and adequately staff correctional libraries. Compounding the problem, in 2015-2016, the Correctional Service of Canada cut their educational spending by 10 percent. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there are no grants in Canada similar to the Pell Grants in the U.S., which provide assistance to prisoners who wish to enrol in an educational program upon release.

Federally sentenced inmates’ maximum daily payment of $6.90 was set more than 30 years ago.

If you’ve been to a federal government office, chances are you’ve used a piece of furniture made by a federal prisoner through the CORCAN program, which produces goods and services for the government and private clients. Prisoners are paid a daily maximum of $6.90 to work within a CORCAN program, or run various parts of the federal institutions where they are incarcerated, including in kitchen, library, and general maintenance roles. By comparison, Matt Torigian, the Ontario Deputy Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services made $620.79 in the first day of 2016. It would take a prisoner at least 318 days to make the same amount. And, while the Deputy Minister got an 11.6 percent raise between 2015 and 2016, and a whopping 87.2 percent raise between 2014 and 2015, prisoners’ wages haven’t increased in 36 years, despite recent raises to Ontario’s minimum wage.

This meagre salary has been frozen since 1981—when it was set as 15 percent of the federal minimum wage. The federal government began automatically deducting 30 percent from that amount in 2013, in addition to removing incentive pay for working with CORCAN, in a move to save costs. Less than nine percent of prisoners even make the maximum amount of $6.90. Thirty-seven percent make $5.80 a day before deductions, and 30 percent make only $2.50. The average before deductions is just $3 per day. Prisoners can reach the maximum amount only after at least a year of working with no absences, no late arrivals, and having “exceeded expectations for interpersonal relationships, attitude, motivation, behaviour, effort, productivity and responsibility.”

Unnecessary and excessive force is used frequently against Canadian prisoners by correctional staff—and disproportionately against racialized inmates and those who suffer from mental health issues.

The use of force against inmates—who are already in a vulnerable position with respect to correctional staff—in Canadian prisons is alarming. Use of force primarily refers to use of inflammatory agents (e.g. pepper spray), but also includes physical handling, use of restraint equipment, use of batons or weapons, or display and/or use of firearms. In 2015-2016 there were 1800 use of force incidents in federal institutions—a 22 percent increase from 2014-2015. Of these incidents, 30 percent involved Indigenous inmates and 18 percent involved Black inmates. Additionally, 36.6 percent of incidents involved inmates with an identified mental health issue. A 2013 investigation revealed a similar trend in Ontario of correctional officers using excessive violence against inmates with a history of mental illness. This investigation also revealed that many correctional staff colluded with coworkers to hide their abusive behaviour against inmates.

In November 2016, there were 22 prisoners in Ontario who had been locked in solitary confinement continuously for more than a year—five of whom had been in solitary for more than three years.

Referred to as “segregation” in Canadian policy, segregation is just another name for solitary confinement. The most commonly used definition of solitary confinement is “the physical and social isolation of an individual for 22 to 24 hours a day." On any given day in Ontario in 2016, 575 people were being held in segregation, with 70 percent of that number on remand. However, as Howard Sapers noted in a March 2017 report titled “Segregation in Ontario,” due to a lack of a precise definition of what segregation is, this number does not encompass how many people are being held in conditions of solitary confinement across Ontario. For example, at Toronto South, there are units called Behaviour Management Units, where–despite not being officially labelled as a segregation unit–prisoners are only allowed out of their cells for 1.5 hours per day, leaving people confined to their cells for the other 22.5 hours. For Adam Capay, an Indigenous man from Lac Seul First Nation who was incarcerated in jails in Thunder Bay and Kenora, 'segregation' meant “being detained in a Plexiglas-lined cell within a windowless segregation unit, illuminated by artificial light 24 hours per day.”

In February 2017, Paul Dubé, the Ombudsman of Ontario, called on the Government of Ontario to create a clear definition of segregation based on the conditions of the unit, rather than the name of the unit, which are selected by institutions themselves. Several months earlier, in December 2016, Koskie Minsky LLP, on behalf of current and former prisoners, launched a class action lawsuit against the Attorney General of Canada for “systemic over-reliance on solitary confinement and failure to provide adequate health care to mentally ill prisoners incarcerated in the Federal penitentiary system.”

Last month, following public outcry and an inquest into the death of Ashley Smith in a segregated cell at the Grand Valley Institution for Women in 2007, the federal government announced a new 15-day cap for solitary confinement for federal prisoners. This will be put in place by Correctional Service Canada after an 18-month transition period (where the cap will be set at 21 days), but as prisoners’ justice advocates are demanding, this should be only the first step towards a total ban on solitary confinement.

In Ontario, excessive lockdowns—or, the practice of confining general population inmates to their cells for up to 24 hours a day—have led to the filing of a class action lawsuit against the Government of Ontario.

Like the class action on solitary confinement, Koskie Minsky LLP is also the firm behind this class action. One of the case’s plaintiffs, Raymond Lapple—who was incarcerated at Maplehurst Correctional Complex from 2009-2013—believes that his post-release diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety were caused “in part by lockdowns at Maplehurst.” Another plaintiff in the case, Jerome Campbell–who was incarcerated at Toronto South for seven months in 2016—provided affidavit stating that lockdowns could last from “one day to two weeks,” and that the institution was locked down approximately 75 percent of the time. Staffing-related lockdowns have been an issue at Toronto South since it first opened in January 2014, with prisoners often being confined to double-bunked cells for four or more days per week, according to lawyers familiar with the institution. In February 2016, a Toronto South security official testified in court that, as far as he was aware, there are no provincial policies that limit the use of lockdowns. Frequent lockdowns at Toronto South have led to prisoner protests in the form of hunger strikes.

Of the incarcerated population, 27.6 percent have an identified mental health need, a rate much higher than in the general population (about 10 percent in 2012). Suicide accounts for about 20 percent of all deaths in custody each year.

Prisoners with a history of self harm are far more likely to be placed in solitary confinement than other inmates (86.6 percent of those with a history of self harm also have a history of being placed in segregation, compared to 48.1 percent in the general population), where they have less access to programming and education, and are subject to increased surveillance. Known as a “prison within a prison,” segregation is harsh, punitive, and a long-identified risk factor in suicide. A Three Year Review of Federal Inmate Suicides (2011-2014) reveals that in 2011, under the Harper government, Correctional Service Canada stopped producing the Annual Inmate Suicide Reports on suicides occurring each year within their facilities. The United Nations Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council has declared the use of segregation in excess of 15 days and the practice of solitary confinement of any duration of mentally ill prisoners a violation of international human rights law.

Information about prisons in Canada is extremely difficult to access

Although the data presented in this piece was entirely taken from public reports, academic research, and news articles, the information was often buried in tables, long documents, and technical terminology. In even more cases, the data simply wasn’t available: where was the data on race, gender, and class disparities in sentencing? Where was the reliable data on how long prisoners are being kept on lockdown or solitary confinement? What we encountered, again and again, was that the information did not exist–in public data sets or in the media.

This lack of public data does not mean that prison staff and administrators are ignorant to the issues within their institutions. In fact, many of the key issues raised in this piece have been examined repeatedly by independent bodies like the federal Office of the Correctional Investigator and Ontario’s provincial Community Advisory Boards. The Toronto South Detention Centre’s Community Advisory Board, for example, reported in 2015 and again in 2016 that prisoners were being subjected to too many lockdowns, inappropriate use of segregation and force, and a lack of adequate mental health care.

The lethal apathy displayed by Canada’s criminal justice systems is not new. Over 40 years ago, on August 10th, 1976, prisoners from Millhaven Institution, a maximum-security prison in Bath, Ontario, staged a one-day hunger strike in remembrance of two prisoners, Edward Nalon and Robert Landers, who had recently died in solitary confinement at Millhaven. The strikers also recognized all prisoners who had “died in the hands of an apathetic prison system” and called on “all concerned peoples of Canada” to support their resistance and lend their voices to the struggle for justice. With International Prisoners’ Justice Day approaching on August 10th, will we become the concerned people that the prisoners of Millhaven called on us to be?

Ways you can support prisoners and prisoner-led initiatives in Canada:

Donate. Fund organizations that support incarcerated and over-policed people in Canada. Some to consider are: Amadeusz, Literal Change*, PASAN, The John Howard Society, Black Lives Matter - Toronto, HALCO, Elizabeth Fry Toronto, and Book Clubs for Inmates. Consider creating a scholarship fund or a specific granting stream for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people in Canada, such as is available in the U.S. through federally funded Pell Grants.

Advocate. Write, tweet, email, or call your local MPs and MPPs about prisoners’ justice issues. Call for educational programs to be implemented for remanded prisoners across the country. Show your support for Howard Sapers’ proposed reforms to solitary confinement in Ontario. Call on the Toronto Police Service to destroy data collected from carding. Support Soleiman Faqiri’s family in calling for the Ontario government to establish clear accountability in Faqiri’s death at the Lindsay Correctional Centre, and signing the family’s petition.

Show your support. Develop a pen-pal relationship with an incarcerated person through organizations like the Prisoner Correspondence Project, or learn how to send books to prisoners.

Learn more. Delve deeper into issues of incarceration in Canada, through resources like these: The Peak’s Dispatches from Prison issue; Toronto Life’s recent feature on Toronto South; Maclean’s deep dive into the over-incarceration of Indigenous people; this article about the late prisoners’ rights and harm reduction activist Peter Collins; striking prisoners at Toronto South; this look into the rampant growth in the number of Black prisoners in recent years; or this article that reveals how Indigenous women have come to form the fastest growing incarcerated group in Canada.

Support prisoners’ legal battles. Follow the two on-going class action cases brought by prisoners against the Government of Ontario for over-reliance on solitary confinement and lockdowns. Help fund an inquest into Errol Greene's death. Consider starting a bail fund or campaign in your community, similar to the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, or Black Lives Matter’s National Mama’s Bail Out Day campaign.

Whenever you hear someone say, “I think incarceration is just a problem in the U.S.,” say something.

About the authors:

Jody Chan is an environmental justice organizer and writer based in Toronto. You can find Jody on Twitter @Jody__Chan. See more of her work at www.jodychan.com.

Lorraine Chuen is a writer, graphic designer, and organizer based in Toronto with an interest in making information about social issues accessible to a wider range of audiences. You can find Lorraine on Twitter @lorrainechu3n.

Marsha McLeod is a journalist focused on sexual violence and non-carceral forms of justice. Marsha is a graduate student at the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University. You can find Marsha on Twitter @marshamcleod_to.

* Marsha was formerly a volunteer for Literal Change. No information used in this piece was taken from the author’s experience in this role, as per her volunteer contract.

Correction: This post has been updated to note that Adam Capay is from Lac Seul First Nation, not Thunder Bay.